Policy Initiatives

NAAA represents the interests of agricultural aviation pilots, operators and allied industry in affecting positive change through education and political action on the national level. The key issues listed here are itemized generally by the Federal Agencies charged with regulating them.

Environmental Issues

NAAA works to educate policymakers and affect congressional and federal agency and judicial decisions to ensure their policies for pest control, plant health, environmental protection, and vector control pertaining to the use of pesticides and fertilizers use the best available science, professional techniques, and modern application technologies used by the aerial application industry; as well as the benefits aerial application provides agriculture and the environment.

The federal requirements for the registration of pesticide products changed significantly when the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA) of 1996 was enacted. The law required all pesticides registered under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) also meet several new safety criteria. These include consideration by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and mitigation of potentially cumulative exposures from direct and indirect methods, such as drinking water, bystander spray drift or residential home and garden uses. FQPA also required additional protection of special subpopulations that may be more susceptible, such as infants and children. The law requires the review every 15 years of all pesticide product registrations, considering any new science or exposure information. The aerial application industry and its customers have been and continue to be affected by FQPA and the registration review process. Under the law, EPA was originally supposed to complete this second FQPA review of all pesticide products before October 1, 2022, but Congress extended the deadline until October 1, 2026 to lessen the threat of legal action.

One of the most critical issues besetting pesticide programs is the implementation of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) into the registration process. Over the past decade, EPA has been sued on numerous occasions for its failure to consult with the Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service (the Services) about the impact of EPA-registered pesticides on endangered species and species habitat. These lawsuits cover hundreds of endangered species and numerous pesticide active ingredients. EPA and the Services have different approaches to pesticide risk assessment and have not been able to resolve their differences despite a continuous effort over the past decade. The Services also lack the resources to complete ESA consultations for all registered pesticide products.

There are several stages during the registration review process. The risk assessments are the first round of documents written by EPA once a product enters the review process. They rely heavily on models to assess the risks pesticides pose to the environment and human health. The proposed interim decisions (PID) are the next phase of the review process. The agency uses the risk assessments as a basis for deciding whether a product should be re-registered and what restrictions should be placed on how it is used. The final interim decision (ID) follows, after the EPA considers comments received on the PID and makes any changes they deem necessary.

The decisions are considered interim instead of a full re-registration of a product because EPA must still complete an Endangered Species Act (ESA) consultation with the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), as well as an endocrine disruptor screen. The ESA requires that EPA work with the Services to evaluate the potential risks each pesticide represents to threatened and endangered species and their designated habitat. The process begins with the EPA conducting a Biological Evaluation (BE) of how the pesticide could impact endangered species. Then the FWS and NMFS issue Biological Opinions (BiOps) that further examine how the pesticide will impact endangered species and their habitats. Once the BEs and BiOps are completed, EPA consults with FWS and NMFS to issue a final decision on re-registration for the pesticide being reviewed. EPA is encouraging registrants to place additional application restrictions on labels up-front to ease the consultation process. NAAA continues to work with registrants, other stakeholders, and EPA to preserve key aerial uses during the registration review process. These include USDA’s Office of Pest Management Policy (OPMP) to assist the office as it weighs in with EPA on product benefits and risk assessments. In addition to working with USDA, EPA, registrants and grower groups, NAAA is represented on the EPA’s Pesticide Policy Dialogue Committee (PPDC). The PPDC is a federal advisory committee that provides a forum for a diverse group of stakeholders to provide feedback to the EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs on various pesticide regulatory, policy and program implementation issues. Stakeholders include academia, state and local regulatory officials, environmental activists, grower groups and pesticide manufacturers themselves.

- NAAA has commented to EPA on the need to use Tier 3 rather than Tier 1 of the AgDRIFT atmospheric software that models aerial pesticide movement after the application. Tier 3, compared to Tier 1, takes into account much more realistic aerial droplet sizes, aircraft, boom drop systems and other setups and practices standard in today’s aerial application industry.

- Commenting to EPA on the need to make all buffer zones wind-directional.

- NAAA has commented to EPA on the need to increase maximum allowed wind speed for aerial applications from 10 mph to 15 mph.

- NAAA has educated EPA about the aerial application industry’s education and training program results. For example, the PAASS (Professional Aerial Applicator Support System) program and Operation S.A.F.E. (Self-regulating Application & Flight Efficiency) fly-ins, C-PAASS (Certified Professional Aerial Applicator Safety Steward)

- NAAA continuously monitors the Federal Register for all new registrations, registration reviews, and other proposed rules to ensure pesticides can be applied by aerial application.

- Since 2017 NAAA has submitted the following to EPA

- Comments for 240 pesticides

- 299 total comments and other letters

- Major policy victories include:

- Many products are now registered with a 15-mph wind speed limit.

- Requires 65% boom for fixed wing aircraft and 75% boom for helicopters in 11 to 15 mph winds

- Requires ¾ upwind swath displacement in 11 to 15 mph winds on downwind edge.

- Use of American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers (ASABE) standard S572.1 to specify the required droplet size on the label instead of language using specific nozzle types and operating parameters which can change with technological advances.

- EPA switching from Tier 1 to Tier 3 model in AgDRIFT

- EPA moving towards wind-directional buffers in almost all cases

- Many products are now registered with a 15-mph wind speed limit.

- Other common aerial restrictions being proposed for labels during registration review process:

- Not spraying during inversions

- Requires 75% boom for fixed wing aircraft and 85% boom for helicopters in winds up to 10 mph

- 1/2 upwind swath displacement in 11 to 15 mph winds on downwind edge

- Maximum application height of 10 feet unless higher is needed for pilot safety

- Chlorpyrifos

- In November 2023 Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals 2021 rule prohibiting chlorpyrifos use on food or feed crops.

- As a result of the above action EPA reinstated all tolerances for chlorpyrifos

- EPA indicated they will move ahead with the 2020 chlorpyrifos PID, released before the 2021 ban

- Restricts chlorpyrifos to the following uses: alfalfa, apple, asparagus, cherry, citrus, cotton, peach, soybean, strawberry, sugar beet, wheat, and wheat (winter).

- Additional mitigations may also be required, including a potential ban on aerial applications.

- Beginning in June of 2024, registrants began voluntarily canceling certain products or amending registrations to restrict their use to the 11 crops

- December of 2024 – EPA released the proposal to revoke chlorpyrifos tolerances for all crops except alfalfa, apple, asparagus, cherry, citrus, cotton, peach, soybean, strawberry, sugar beet, wheat, and wheat (winter). The revised PID is expected in 2026.

- 2025 – NAAA submitted comments on EPA’s proposal to revoke tolerances to all but the above mentioned 11 crops highlighting the importance of aerial applications of chlorpyrifos and recommending EPA reconsider the revocation, particularly for corn and sunflowers

- Paraquat

- In 2021 PID for paraquat proposed banning all aerial applications of paraquat

- After NAAA comments, final ID allows aerial but limits many applications to 350 per day per pilot for all aerial applications except cotton and soybean desiccation. This was based on inhalation concern for pilots.

- In 2024 NAAA commented to an EPA reconsideration on paraquat ID asking EPA to increase allowable daily acres aerial applications of paraquat for herbicidal uses.

- New Weather measuring requirements in fall of 2023.

- Weather forecast must be checked 12 hours before application.

- Wind speed and direction must be measured on site at the application height

- Must be rechecked every 15 minutes during application.

- Dicamba

- 2025- NAAA commented on the proposed registration of three new formulations of dicamba for use on dicamba tolerant crops. As in the prior attempts to register these products for dicamba tolerant crops, aerial application was prohibited. NAAA commented in favor of allowing aerial application, focusing on the importance of timely applications and drift mitigation options, as detailed in the herbicide strategy, that would allow aerial applications to be made safely. Grower groups, such as the American Farm Bureau Federation were also interested in NAAA’s position and supported NAAA’s position that aerial application should be allowed for over the top dicamba applications.

- EPA resolved longstanding litigation (megasuit) covering over 1,000 pesticide products, allowing EPA to fulfill its obligations to protect endangered species while conducting reviews and approvals of pesticides. It Required EPA to develop mitigation measures as detailed in ESA workplan, vulnerable species pilot project (VSPP), herbicide strategy, and forthcoming rodenticide strategy, insecticide strategy, and fungicide strategy which will identify ESA mitigation measures for entire classes of pesticides.

- NAAA ensured aircraft smokers and other types of meteorological measuring technology can be used to verify wind; now on labels

- ESA Workplan – lays out plan for EPA to improve EPA’s efficiency with meeting its ESA obligations and reduce the need to consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service.

- Result of settlement agreement in the “Mega Lawsuit”, filed by numerous environmental activists groups alleging EPA has failed to abide by ESA.

- ESA Workplan update

- Details how pesticide labels will use Endangered Species Bulletins Live! Two (BLT) website to show applicators’ location of ESA pesticide use limitation areas (PULA) are located and provide access to any additional mitigations needed when applying near the species.

- Proposes use of wind-directional buffers

- Vulnerable Species Pilot Project (VSPP): focused on a group of 27 species that are particularly vulnerable to harm from pesticides; NAAA submitted comments.

- Some PULAs would be specific, others vague.

- Proposed wind-directional buffers

- Acknowledged need to move from Tier 1 to Tier 3 in AgDRIFT

- Update based on public comments narrowed species range maps, clarified non-ag uses, and revised mitigations.

- Herbicide strategy

- Draft released in July 2023; NAAA submitted comments

- Protect ESA species and habitat from herbicides in lower 48 states

- Drift mitigations proposed for aerial applications focused on wind directional buffer zones

- Uses BLT to show PULAs and access bulletins with mitigations

- PULAs unnecessarily large – based on range instead of locations; would increase cropland affected by ESA mitigations

- Update released in 2024 suggesting refined PULAs and move to Tier 3

- Final strategy released in August of 2024

- All buffer zones downwind

- Distance based on risk of species and pesticide in question; will range from 50 to 320 feet.

- Buffer distances can be reduced by increasing droplet size, using a drift reduction adjuvant, when applying to a small field only requiring a few passes, when there is a windbreak or similar vegetative barrier present, and when humidity is higher than 60%.

- Managed areas such as other fields, roads, managed wetlands, field borders, etc. can all be included as part of the buffer

- Mitigations and managed areas will be expanded upon as new data becomes available.

- Hawaii strategy – because of its unique nature, Hawaii is receiving an ESA strategy specific to it. NAAA assisted USDA OPMP in determining the extent of aerial applications in Hawaii

- Once finalized, strategies will be implemented as part of registration review or new registration process for every pesticide.

- Insecticide Strategy

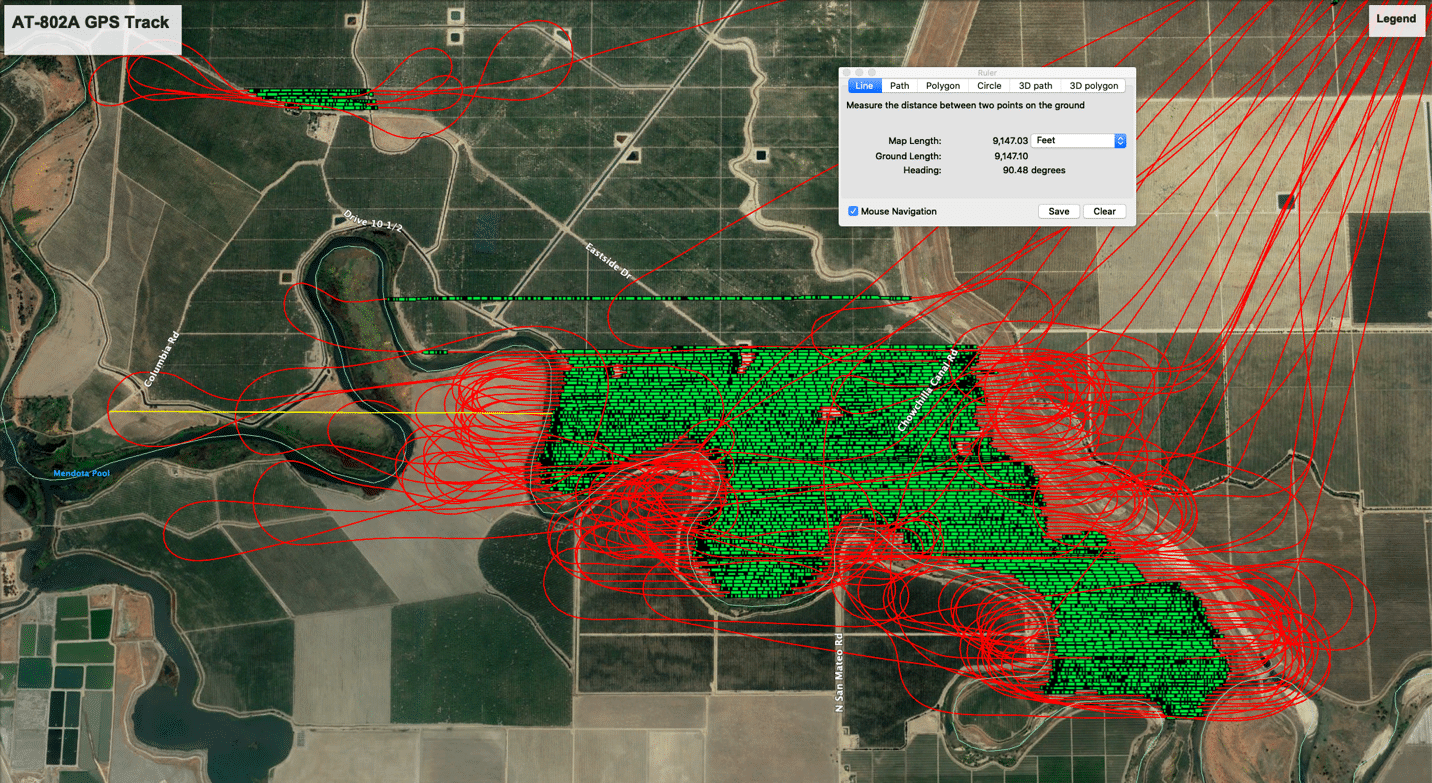

- July of 2024 – draft insecticide strategy released – it was very similar to the final herbicide strategy. Wind directional buffer zones, distance can be reduced by using mitigations including larger droplets, and managed areas will count as part of buffer. NAAA requested boom length reductions be added as a drift mitigation option. The ecological mitigation support document that was released with the insecticide strategy finally accepted NAAA’s recommendations to switch from the Tier 1 to the Tier 3 AgDRIFT model and improve the assumptions. EPA changed the default aircraft to an AT-802 with a corresponding increase in swath width and decrease in the number of passes. The default droplet size was increased to medium, atmospheric stability was set to a level that rules out the presence of an inversion. EPA also changed the height at which wind speed is measured to reflect smokers and onboard meteorological measurement systems and increased the upwind swath displacement to reflect what is actually practiced in the industry. There were two assumptions EPA did not agree with completely on with NAAA – surface roughness and standard boom drop. While EPA did not agree with the values proposed by NAAA, they did not disagree with the logic behind our recommendations.

- April 2025 – final insecticide strategy released. Wind directional buffer zones are the mitigation option to reduce risk of drift. They can be on label to protect unmanaged areas and on BLT to protect PULAs. Maximum buffer distance is 300 feet for aerial applications; reduced by mananged areas as part of buffer and drift mitigation measures. Each mitigation measure is assigned a percentage reduction for buffer distance; perccentages are cumalitive. It is possible to eliminate the need for a buffer by either managed areas or mitigation measures. See www.epa.gov/pesticides/mitigation-menu for current ist of managed areas and mitigation measures. The use of a website instead of label will allow new application technologies to be added for buffer reduction measures. Growers will need to comply with a mitigation system to reduce off site exposure from runoff/erosion. Commerical applicators will need to require customer records for their application records to confirm compliance. EPA is working on refining the size and scope of PULA’s to better reflect locations where endangered species actually occur.

- 2025 – NAAA worked with Syngenta to support aerial applications for their new insecticide isocycloseram. This registration used the recently finished insecticide strategy. EPA’s initial registration proposal was only going to allow aerial applications of the insecticide on cotton. NAAA provided data to support aerial applications for all crops. The proposed registration approval was released in May of 2025; EPA proposed to approve aerial applications of isocycloseram for only corn, soybean, potatoes, and cotton. For corn and soybean, aerial applications would only be allowed in a limited number of states. For corn, aerial application of isocycloseram would only be allowed in CO, KS, NE, OK, and TX; for soybean, aerial applications would only be allowed in AL, AR, GA, LA, MS, MO, NC, OK, SC, TN, and TX. NAAA commented on the need for aerial application of isocycloseram on corn and soybeans in all states and how the insecticide strategy would allow these applications to occur and protect endangerd species.

- EPA’s BiOp for carbaryl proposed a 150-foot non-wind directional buffer zone for aquatic areas for aerial applications; it’s 25 feet for ground applications. It was unclear if the buffers were intended to protect against runoff, drift, or both. NAAA commented that all drift reduction buffer zones should be wind directional, and that if the buffer is intended to protect from runoff there should be no difference between buffer distance for ground and aerial. The issue of non-wind directional buffers for aqutic areas is expected to continue to be an issue.

- Isocycloseram was registered in November 2025. All of the proposed aerial prohibitions and restrictions from the proposed registration were kept in the final registration. NAAA will continue to work to increase the types of crops and the states for aerial applications of isocycloseram.

- NAAA commented in favor of the registration for a new herbicide, epyrifenacil; all proposed drift mitigations are acceptable expect one. NAAA objected to the statement “When applying to crops via aerial application equipment, the spray boom must be mounted on the aircraft to minimize drift caused by wing tip or rotor blade vortices” as being vague. NAAA also objected to a minimum spray application rate of 7 gallons per acre (GPA). NAAA commented on the atrazine BiOp, supporting the proposed aerial drift mitigations.

FIFRA for decades regulated at the federal level all aspects of pesticide use, and it was, until 2009, uncommon for Clean Water Act (CWA) rules to come into play for the aerial application industry—for example, avoiding applications outside of buffer zones set up around specific aquatic habitat and wetlands, or to impaired river segments or lakes covered by Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) designed to help meet state water quality standards. However, a 2009 decision of the Sixth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals (National Cotton Council, et al., v. EPA) brought the full weight of the CWA into the realm of FIFRA and aerial application businesses. With this ruling, pesticide applications made into, over or near “waters of the U.S.” according to FIFRA product labels must also comply with the additional requirements of an NPDES pesticide general permit (PGP).

As much as aerial and ground contract pesticide applicators were affected by this ruling, government agencies with pest control responsibilities are even more affected. These include primarily federal, state, and municipal water programs and pest control agencies, for they are the “decision makers” who must comply with the broadest range of PGP requirements. Also, in this group can be public health agencies and mosquito control organizations; wildlife agencies and large aquatic weed control companies; irrigation districts; managers of highways, roads and utility rights-of-ways; and forest and park managers. Obviously, there is a lot of shared burden, especially for a permit that most states agree contributes little environmental benefits over existing FIFRA and state pesticide programs.

The types of pesticide applications that are regulated by the permit include: mosquito and other flying insect pest control; weed, algae and pathogen pests in waters at water’s edge, including ditches and/or canals; animal pest control in water and at water’s edge; and forest canopy pest control where a jurisdictional waterbody is under the canopy and may be affected by the applied pesticides. Some state PGPs add other covered uses, such as for control of weeds on right-of-way or in rangeland. An explanation of the types of parties that are likely to fall into these use categories is available on EPA’s pesticide permitting webpage.

To meet the court’s requirement, EPA and 45 separate states first developed PGPs in 2011 and have been implementing them since. These five-year permits vary widely in requirements. On October 31, 2021, EPA reissued its PGP for another five-year cycle and an updated PGP proposal has recently been proposed. Permit fees vary from a few hundred dollars to over $1,000 in some states, and PGPs have increased compliance costs and manpower resource needs for all involved. Worse than these costs, however, is the legal risk – failure to comply with the permits can result in hefty agency fines and penalties, as well as potential citizen suits over alleged violations. For the states in which NAAA members operate, it is imperative aerial applicators know what is needed to avoid violating these PGPs and triggering enforcement action, or worse, citizen suits.

State PGPs differ significantly: EPA’s PGPs regulate pesticide applications in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, and Idaho and the District of Columbia; all U.S. territories except the U.S. Virgin Islands; federal facilities in Delaware, Vermont, Colorado, and Washington; discharges in Texas that are not under the authority of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, including activities associated with oil and gas exploration; and all areas of Indian Country that are not covered by an EPA-approved permitting program. The other 44 states not covered by EPA’s PGP have some form of state PGP in place, but they do vary considerably. That means if you have pesticide applications that extend across state borders you may need to comply with a number of different PGP requirements.

State PGPs fall into three categories: 1) PGPs which have extensive compliance requirements for all dischargers (e.g., NY, CA, KY, WA, WI); 2) PGPs which extend automatic coverage and legal protections to all operators as long as they meet permit conditions (e.g., LA, SD, MD, VA, ND, CO); and 3) PGPs that only have extensive requirements for government agencies and other large entities whose pesticide applications exceed annual treatment thresholds, but modest requirement for others below annual thresholds (e.g., FL, IA, OH, SC, PA, OR). In an effort to compare state permits, NAAA has analyzed each state’s permit and contrasted them in a chart.

It is important aerial applicators know which PGP requirements apply to their businesses. To help educate members, NAAA has developed a comprehensive document that outlines aerial applicator’s obligations under the NPDES pesticide general permit. In the PGP, applicators have less burdensome requirements than government agencies, landowners, and other major pest-control decision-makers who have control over pesticide applications into, over or near US waters. However, if an aerial applicator makes the pesticide application decisions for his clients, that applicator may become a “decision-maker” and then must comply with all applicable requirements imposed on both applicators and decision-makers. It is important that aerial applicators know what distinguishes the requirements of “for-hire” applicators from those of “decision-makers.” Thus, operators and their clients should have an agreement in place clearly delineating the role of the client decision-maker and applicator for each application made. To assist NAAA members, NAAA has developed sample contract language for reference when preparing contract negotiation with clients delineating that the aerial applicator is not the decision-maker.

In November 2023, EPA released the draft 2026 PGP. On October 4, 2021, the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD) filed a petition for review with the Ninth Circuit regarding the 2021 Pesticide General Permit (PGP). EPA, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, and CBD entered into a settlement agreement on July 25, 2023 to resolve the litigation. On December 19, 2024, CBD filed a consent motion to voluntarily dismiss the appeal. As part of the Settlement Agreement, EPA agreed to issue the final 2026 PGP on or prior to December 17, 2024. The permit would still take effect October 31, 2026, when the current 2021 PGP expires.

NAAA’s commented on the 2026 draft and its comments were like its earlier comments and touched on the redundancy of the PGP, considering that all pesticides, including those for aquatic sites, already undergo a registration and then a reregistration review process to verify their safety to the environment when used according to label directions. NAAA did point out that Endangered Species Act (ESA) requirements on the PGP are yet another redundancy considering EPA’s recent spate of efforts to address ESA issues in pesticide registration and review processes. NAAA also expressed concerns about updated site monitoring and record keeping requirements, some of which fall on the applicator. NAAA pointed out these requirements have the potential to be overly burdensome to aerial application operations, many of which are small businesses. Other industry comments also urge the EPA to eliminate joint and several liability provisions from the PGP, as they set a concerning precedent for their activities. Also, requests were made for clarification that the PGP does not apply to stormwater discharges that do not currently require an NPDES permit.

Notable changes in the draft 2026 National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Pesticide General Permit (PGP) compared to the 2021 PGP. Key proposed modifications include Enhanced Visual Monitoring and Documentation:

- Introduction of Part 4.3, “Documentation of Visual Monitoring,” emphasizing the requirement to record visual monitoring activities as outlined in Parts 7.2, 7.3, and 7.4.

- Addition of Part 4.4, “Additional Monitoring,” highlighting that EPA may mandate further monitoring to ensure compliance with the PGP.

- Requirement for Decision-makers to submit a Pesticide Discharge Management Plan (PDMP) alongside their Notice of Intent (NOI) as specified in Part 5.

- Inclusion of visual monitoring procedures within the PDMP content requirements.

- Mandate that records of visual monitoring include specific details such as date, time, and location.

- Obligation for Decision-makers to submit visual monitoring records with their Annual Report.

All PGPs include these minimum requirements:

- Carefully handle and store pesticide products to avoid leaks and spills

- Promptly deal with spills following manufacturer recommendations

- Comply with the FIFRA labels on products they are hired to apply

- Properly mix and load pesticides into their aircraft

- Properly rinse and recycle/dispose of empty pesticide containers

- Properly clean their spraying system after application

- Preventatively maintain those pesticide-application systems to avoid leaks

- Calibrate aircraft spraying systems so they apply the proper amount of pesticides

- Properly identify and direct the application to desired boundaries using GPS when feasible or on-ground flagging

- Properly apply the pesticide products to the appropriate location and at the proper rate

- Keep proper records of all regulated activities

- Communicate this information to clients in a timely manner for the permit compliance needs of those organizations

- Monitor equipment during application to ensure proper functioning and to avoid off-target application. Records of these activities are necessary, as are spray logs.

NAAA has prepared a checklist of compliance activities for aerial applicators’ aid in complying with this burdensome task. Should an applicator determine that the manner in which any of these activities is performed is not satisfactory, or should an adverse incident occur for an applicator, the practices would need to be upgraded before the next pesticide application, and any adverse impact reported to the EPA or the state permitting agency.

Efforts to encourage Congress to address legislative fixes to NCC vs. EPA by NAAA and its ag/pesticide user stakeholder coalition have been underway since the court’s decision in 2009. The House has passed legislation, titled the Reducing Regulatory Burdens Act, that would create a legislative exemption for NPDES permitting of pesticides several times as either free standing legislation or part of various iterations of House Farm Bills. NAAA is working to get NPDES permit relief included in the 2025 Farm Bill.

The CWA does not define WOTUS; since the 1970’s, the EPA and Army have defined it by regulation. Four Supreme Court decisions addressed the definition over the years. The 2015 Clean Water Rule wholly redefined WOTUS but was repealed by a 2019 Rule which reinstated the prior regulations, implemented consistent with the Supreme Court decisions and applicable guidance. However, the 2019 Rule was replaced with the Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR) in 2020, which itself had implementation halted in 2021 due to other litigation.

The “Revised Definition of ‘Waters of the United States’” rule took effect on March 20, 2023 being codified in place of the NWPR. However, effective September 8, 2023, the EPA amended this rule to conform to a Supreme Court decision invalidating the “significant nexus standard” test to identify waters that, either alone or in combination with similarly situated waters in the region significantly affect traditional navigable/interstate waters.

EPA released a proposal to update the definition of Waters of the United States (WOTUS) in November of 2025 that attempts to reduce regulatory burdens and associated costs with compliance. To achieve these aims, EPA proposes narrowing the scope of jurisdiction to relatively permanent waters and wetlands that maintain a continuous surface connection to such waters. The rule also refines key terms, including “relatively permanent” and “tributary,” and clarifies long-debated exclusions for features such as certain ditches, prior converted cropland, waste treatment systems, and groundwater. EPA maintains that these updates directly address longstanding stakeholder requests for clearer, more predictable standards that lessen compliance uncertainty and litigation risk. The agency defines “relatively permanent” to mean “standing or continuously flowing bodies of surface water that are standing or continuously flowing year-round or at least during the wet season.” The agency defines “tributary” to mean “a body of water with relatively permanent flow, and a bed and bank, that connects to a downstream traditional navigable water or the territorial seas, either directly or through one or more waters or features that convey relatively permanent flow.” Further, the proposed definition of “tributary” clarifies that a “tributary does not include a body of water that contributes surface water flow to a downstream jurisdictional water through a feature such as a channelized non-jurisdictional surface water feature, subterranean river, culvert, dam, tunnel, or similar artificial feature, or through a debris pile, boulder field, wetland, or similar natural feature, if such feature does not convey relatively permanent flow.

EPA also underscored the rule’s economic implications, noting that improved regulatory clarity stands to benefit farmers, ranchers, and developers who rely on consistent water-related permitting frameworks. The proposal, if made permanent and remains unchanged by subsequent administrations, will reduce the areas required to obtain a pesticide general permit under the Clean Water Act’s National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES). NAAA will continue to advocate for changes to the rule that provide additional clarity for our members about which waters are subject to federal regulation, including NPDES permits.

To protect the public’s health, and to protect farmers from unnecessary and burdensome regulations stymying them from producing food, fiber, and biofuel, NAAA urges Congress to exempt applications of EPA-approved pesticides from the NPDES pesticide general permit requirements.

On December 11, 2025, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 3898, the “Promoting Efficient Review for Modern Infrastructure Today (PERMIT) Act” (HR 3898), which among other permit reforms, would clarify that NPDES permits are not needed for applications for EPA registered pesticides. The legislation was championed by Rep. David Rouzer (R-NC), House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee Water Resources and Environment Subcommittee Chairman Mike Collins (R-GA) and other committee leaders. NAAA encourages the Senate to take similar action. NAAA also supports and advocates for the inclusion of NPDES permit relief in the next Farm Bill or any other appropriate legislation.

|

2025-12-18 | |

|

2025-12-04 | |

|

2025-06-26 | |

|

2024-02-01 |

Clean Water Act NPDES PGP Exemption Legislation Begins to Trickle Its Way Through Congress |

|

2024-01-18 |

NAAA Submits Comments to EPA on Agency’s Third Proposed NPDES PGP |

|

2023-09-14 |

EPA Releases Amended WOPTUS Definition in Aftermath of Supreme Court’s Narrowing Ruling Last Spring |

|

2023-08-10 | |

|

2023-06-15 | |

|

2023-06-08 |

NAAA Urges EPA to Reject Settlement Adding More Redundancy to NPDES Pesticide General Permit |

|

2023-05-04 | |

|

2023-04-06 |

Texas Court Issues Injunction Prohibiting Biden Administration’s WOTUS Definition in Texas and Idaho |

|

2023-02-16 | |

|

2023-01-19 |

Biden Administration Releases Its Rule Defining ‘Waters of the U.S.’ Under the Clean Water Act |

|

2022-09-29 | |

|

2022-06-30 | |

|

2022-04-21 |

EPA Releases Strategy to Accelerate Nutrient Pollution Reductions |

|

2022-02-25 |

NAAA Comments on Biden Administration’s Redefinition of the Clean Water Act’s Waters of the U.S. |

|

2022-02-03 |

Supreme Court to Hear Case Questioning Reach of Clean Water Act |

|

2022-01-27 |

PFAS have presented liability issues for manufacturers for decades and now, the issue has become of increasing concern to agriculture. PFAS is used in non-stick cookware, food packaging, water-repellent apparel, stain-resistant carpet, and hundreds of consumer and industrial goods and applications. PFAS (pronounced PEA-fass) are a broad class of synthetic chemical compounds, currently estimated to number around 10,000. So called “forever chemicals” because of their bio-accumulative properties and persistence in the environment over time, PFAS have widely been used in the U.S. and around the world since at least the 1940s. They are found in water, soil, air, and plants and detected in the blood of humans, animals, and fish. Some are known to be “toxic,” and have been linked to cancer, developmental disruptions, and other adverse health conditions. Since 1999, tens of thousands of lawsuits have been filed against chemical companies over PFAS exposure. Legislation and regulatory activity have increased, with states imposing bans and EPA implementing policies. The definition of pesticides as PFAS could potentially jeopardize their availability and create additional liability. For the aerial application industry, the concern around PFAS rules relates to the presence of PFAS in fluorinated high-density polyethylene (HDPE) containers and the use of PFAS for inert ingredients in manufacturing certain pesticide formulations. There are two fronts to the PFAS issue for aerial and other pesticide applicators – the first is eliminating the use of PFAS in the production of pesticide containers and formulations. The second is ensuing aerial applicators are not exposed to litigation as a consequence of applying pesticides that contained trace PFAS amounts, either from container leaching or in the pesticide formulations.

- In 2021 the EPA released its Strategic Roadmap through 2024, outlining key actions the agency would be taking to address issues around accountability and the human health and environmental impacts of PFAS. The EPA’s strategic roadmap on PFAS was released, detailing the number of regulatory steps the agency has taken so far.

- In March of 2021 EPA released data showing PFAS contamination from the fluorinated HDPE containers used to store and transport a mosquito control pesticide product.

- In September of 2021 EPA released a method to pesticide manufacturers for detecting PFAS in pesticide products formulated in oil, petroleum distillates, or mineral oils. EPA used the method to determine no PFAS were present in three formulated mosquito control products.

- In March of 2022 EPA provided information to manufacturers of HDP) containers and similar plastics about the potential for PFAS to form and migrate from these items. EPA issued an open letter to raise awareness to industry of this issue in order to help prevent unintended PFAS formation and contamination and to outline certain requirements under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) as it relates to PFAS and fluorinated polyolefins.

- In September of 2022 EPA released results from its evaluation on the leaching potential of PFAS from the walls of certain fluorinated HDPE containers into the liquids stored in those containers. Results from this study indicated that PFAS present in the inside walls of the fluorinated HDPE containers can be readily leached into formulated liquid products.

- In May 2023 EPA released laboratory results related to the analysis of ten pesticide products reported to contain PFAS residues. EPA did not find any PFAS in the tested pesticide products, differing from the results of a published study in the Journal of Hazardous Materials. EPA is also released a newly developed analytical methodology used in the testing process alongside the summary of its findings.

- In 2023 the Senate released for public comment a draft bill (S.1427 – Agriculture PFAS Liability Protection Act of 2023) that seeks to protect passive receivers, like farms, from PFAS lawsuits. Of particular significance, though, is the provision to establish a federal definition of PFAS, providing clarity, consistency, and more predictability for industry and stakeholders. Although pesticides are not explicitly mentioned in the bill, crop protection advocates point out that FIFRA regulations already subject pesticides to rigorous scientific testing and therefore, should be excluded from added product regulatory consideration. Cynthia Lummis (R-WY) also introduced a PFAS exemption bill to protect industries like agriculture from Superfund PFAS liability claims

- In February of 2024 EPA released a robust and validated method manufacturers can use to test for 32 PFAS directly from the walls of containers made from high-density polyethylene (HDPE). This method allows industries that use HDPE containers and container manufacturers to test the containers before use, preventing PFAS contamination of products stored in these containers.

- In July 2024 EPA granted a petition from numerous environmental groups to address PFAS used in a variety of plastic containers, including those used to store pesticides.

- Many states are not waiting for the federal government to develop a clear and concise definition of PFAS and are forging ahead with their own definitions and regulatory schemes. Outright bans on a wide range of products containing PFAS have been imposed in Maine, Minnesota, and Washington, and at least ten other states have passed limited scope bans, phase outs, or caps on the amounts of allowable PFAS. With state legislative sessions ramping up or preparing to begin, we are already seeing concerning prohibition bills in New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Vermont.

- In October of 2024 USDA-ARS stated that that their “data shows that PFAS is an environmental hazard that does not come from agriculture”.

- EPA’s 2025 PFAS efforts focused on drinking water standards.

EPA has focused on refining PFAS reporting rules, proposing exemptions for small quantities and specific activities to ease the Toxic Subtances Control Act (TSCA) reporting burden. They also awarded research grants for agricultural PFAS studies in Texas in November 2025, aiming for more practical data collection.

The issue of drift remains a top concern for the aerial application industry. NAAA monitors EPA’s registrations, registration reviews, and other proposals to ensure drift from aerial applications is accurately modeled and all proposed mitigations are acceptable to the industry. NAAA also monitors activities from numerous other organizations in order to stay up to date on the latest in drift mitigation technologies, standards and policies proposed that could affect aerial applications, and efforts outside of the normal EPA Office of Pesticide Program channels that can affect how drift is assessed or mitigated.

- USDA-ARS AATRU corrected ASABE standard S641 Droplet Size Classification of Aerial Application Nozzles to ensure new standards didn’t change the classification of aerial nozzles from original S572.1; i.e. if a nozzle and its operational parameters had been classified as medium using S572.1, then S641 should also classify it as a medium.

- Administrative control of AGDISP, the parent model of AgDRIFT, was transferred from USDA Forestry Service (FS), under the direction of Dr. Harold Thistle, formerly of the USDA FS, to USDA-ARS Aerial Application Technology Research Unit under the direction of Dr. Brad Fritz following Thistle’s retirement.

- In 2020 the company responsible for writing AgDISP, Continuum Dynamics, moved to a paid subscription-based service for future updates of AGDISP. Since AGDISP was publicly funded, Thistle procured a copy of the latest code for AgDISP but Continuum Dynamics stripped all descriptive information from the code making it difficult to interpret.

- With approval by the NAAA Precision Agriculture Committee, NAAA facilitated the creation of a working group to update the AGDISP model. The project has three main objectives:

- Convert the software into a modern computer programming language that is publicly available.

- Improve the accuracy of the model by factoring in changes in several parameters that change during flight such as aircraft weight and AOA.

- Create a real-time version of the model that could be integrated into ag aircraft GPS to provide real-time and site specific drift modeling in flight.

- AGDISP Modernization Project (AMP)

- EPA has indicated support for updating AGDISP.

- A statement of work and cost estimates were prepared; the project is estimated to cost $600,000.

- NAAA is working with registrants, and ag groups for overall support of the AGDISP update and to solicit for funding.

- The CDC, via application technology consultant Dr. Jane Bonds, has agreed to partially fund the AGDISP project for work they’re doing for mosquito control at $250,000 over five years. NAAREF has contributed $50,000.

- A stakeholder review committee has been established and includes representatives from registrants, the EPA, the USDA, grower groups, and other agricultural associations.

- AMP was awarded $35,000 from The Cotton Foundation

- The update to the models programming language continues.

- EPA’s drift mitigation efforts are focused on ESA strategies. No additional drift mitigation policies or programs are expected

- 2025 The USDA-ARS Aerial Application Technology Unit updated their spray nozzle models and added two new nozzles.

- 2025 – The Unmanned Aerial Pesticide Application System Task Force (UAPASTF) submitted the first-ever Good Laboratory Practices (GLP) data from spray drift field trials using UASS.

- AMP was awarded $35,000 from the National Corn Growers Association. The coding process is expected to begin in March 2026.

- Dairyland Aviation in Wisconsin has begun using an onboard weather measurement system, GPS with the original version of AGDISP, and pulse width modulation nozzle control in combination to predict spray movement in the cockpit and adjust spray passes based on the prediction. Dairyland Aviation will be working with the FWS on a pilot project to explore how this and future advancements can protect endangered species.

|

2026-02-06 | |

|

2025-10-02 | |

|

2025-09-25 |

NAAA AGDISP Press Release Earns Media Coverage; NCGA Contributes to Project |

|

2025-09-18 | |

|

2025-08-28 |

NAAA Led AGDISP Modernization Project Awarded Funding from The Cotton Foundation |

|

2025-08-21 | |

|

2025-05-15 | |

|

2025-05-01 | |

|

2024-10-03 |

NAAA Announces EPA’s Change in Aerial Drift Model Use Through Press Release to Agriculture Media |

|

2024-09-26 |

EPA Accepts NAAA’s Recommendations to Improve Accuracy of Aerial Drift Model |

|

2024-04-18 |

EPA Leadership States Movement Towards More Realistic Refinement and Use of Aerial Drift Model |

|

2024-03-28 |

Idaho Enacts Law Punishing Claimants Making Wrongful Drift Allegations |

|

2023-08-10 |

EPA Publicly Acknowledges Points NAAA Has Repeatedly Made About Aerial Drift Mitigations |

|

2023-03-30 | |

|

2022-07-14 |

NAAA Presents at Endangered Species and Pesticide Modeling Meeting |

On September 28, 2015, EPA finalized extensive revisions to its Worker Protection Standards (WPS) under FIFRA, the first major change to these regulations since 1992. EPA stated its proposal was necessary to reduce the incidence of preventable occupational pesticide exposure and pesticide-related acute and chronic illnesses among agricultural workers (workers) and pesticide handlers (handlers). There were several concerns with the revisions, on which NAAA commented concerns with:

- Requiring a 100-foot aerial entry restriction area around fields at the time of application regardless of wind direction;

- Requirements for exchanged communication by an applicator to the farmer within two hours of any programmatic changes to the application;

NAAA also worked with the U.S. Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Office of Advocacy (Advocacy) on their comments on the WPS. When the rule was finalized, several of the concerns NAAA had expressed in comments had been corrected.

- Annual mandatory training to inform farmworkers on the required protections afforded to them.

- Children under 18 are prohibited from handling pesticides; exemption for farm owners and their immediate families with an expanded definition of “immediate family.”

- Expanded mandatory posting of no-entry signs for the most hazardous pesticides.

- Requirement to provide more than one way for farmworkers and their representatives to gain access to pesticide application information and safety data sheets – centrally-posted, or by requesting records.

- Records of application-specific pesticide information, as well as farmworker training, must be kept for two years.

- Anti-retaliation provisions are comparable to Department of Labor’s (DOL).

- Changes in personal protective equipment will be consistent with DOL’s standards for ensuring respirators are effective, including fit test, medical evaluation and training.

- Specific amounts of water to be used for routine washing, emergency eye flushing systems and other decontamination, for handlers at pesticide mixing/loading sites.

- The Application Exclusion Zone (AEZ) – a circular area around the sprayer that moves with the sprayer. If someone enters the AEZ, then the pesticide applicator is required to stop the application.

- The 2015 draft AEZ rule required applications to be suspended when any persons enter the AEZ (100-foot radius for aerial applications), even if they are outside the property being treated.

- The final rule was released in 2020 and removed AEZ applicability outside the boundary of the property being treated as well as clarifying when applications can resume based on comments from NAAA and other ag groups.

- Following the publication of the final rule, EPA was sued in two separate cases over the changes to the AEZ; the 2020 revision was stayed by court action.

- In March 2023, based on the lawsuits, EPA released a reconsideration that reverted back to the original 2015 requirements; NAAA opposed using same arguments from 2015 and also arguing AEZ should be based on wind direction.

- In September 2024, EPA finalized the AEZ rule, reverting the AEZ to as it was originally established in 2015 which includes the following provisions:

- When any person(s) enters the AEZ, the pesticide applicator must immediately suspend the application.

- The AEZ extends beyond the boundaries of the agricultural establishment – it doesn’t matter whose property the person(s) is on, the application must be suspended

- The AEZ also includes all easements on the establishment (for example, easements for utility workers to access telephone lines).

- The AEZ distance for aerial applications is 100 feet regardless of droplet size or wind direction.

- Farm owners and immediate family members are exempt provided they are within an enclosed building during the application

- The application cannot be resumed until the person(s) has left the AEZ.

- These reduced exposure values will be favorable to aerial application when EPA conducts occupational health risk assessments.

In May 2021 EPA updated the Occupational Pesticide Handler Exposure Calculator and Occupational Pesticide Post-Application Exposure Calculator with new data:

- Include new exposure estimates from Agricultural Handler Exposure Task Force (AHETF) for dermal and inhalation exposure for workers using closed systems

- The more accurate data showed reduced exposures for dermal and inhalation exposures for both liquid and dry formulations.

In 2025 NAAA assisted Unmanned Aerial Pesticide Application System Task Force (UAPASTF) with a survey of part 137 UAS operators to assess exposure risks for UAS handlers, pilots, and mixer-loaders.

N/A

In 2018 EPA finalized a rule for certification for commercial and private applicators of Restricted Use Pesticides (RUPs), and any non-certified applicators working under their direct supervision.

- Specialized certification requirements for aerial application, soil fumigation, and non-soil fumigation.

- Persons must be at least 18 years old to qualify as a non-certified applicator using RUPs (Exception: persons under the supervision of an immediate family member and applying non-commercially must be at least 16 years old.)

- Certifications are now valid for a maximum of five years,

- Required pesticide certification at least once every five years through either written exams for each certification or by completing specific training in a continuing education authority for commercial applicators.

- Requires states to adopt Continuing Education Unit (CEU) criteria for the quantity, content, quality assurance of CEUs, and verification of completed CEU coursework.

- Allow states to choose between requiring recertification by exam or completion of CEUs.

- States must require commercial applicators to maintain application records for a minimum of two years; records must include:

- the name and address of the person for whom the pesticide was applied;

- The location and size of the pesticide application area

- Time and date of application

- Product name and EPA registration number of RUP applied

- Total amount of the pesticide applied

- The name and certification number of the certified applicator that made or supervised the application, and if applicable, the name of any non-certified applicator(s) that made the application under the direct supervision of the certified applicator.

- Requires State certification plans to address reciprocity with other states.

- Defines “use” as in “to use a pesticide” to include any pre-application activities (including arranging for application and mixing and loading), applying the pesticide or supervising use by non-certified applicator, transporting or storing pesticide containers that have been opened, cleaning equipment, disposing of excess pesticides, spray mix, equipment wash waters, pesticide containers, and other pesticide-containing materials.

- Labeling – Label requirements specific to aerial application including:

- Spray volumes

- Buffers and no-spray zones

- Weather conditions specific to wind and inversions

- Application equipment – Understanding of how to choose and maintain aerial application equipment including:

- The importance of inspecting equipment prior to use

- Selecting the proper nozzles

- Knowledge of the components of an aerial application system including hoppers, tanks, pumps and nozzles

- Interpreting a nozzle flow rate chart

- Determining the number of nozzles for intended pesticide output using nozzle flow rate chart, aircraft speed and swath width

- How to ensure nozzles are placed to compensate for uneven dispersal due to uneven airflow from wingtip vortices, helicopter rotor turbulence and aircraft propeller turbulence

- Where to place nozzles to produce the appropriate droplet size

- How to maintain the application system

- How to calculate the required and actual flow rates

- How to verify flow rate using fixed timing, open timing, known distance or a flow meter

- When to adjust and calibrate equipment

- Application considerations – The applicator must demonstrate knowledge of factors to consider before and during application, including all the following:

- Weather conditions that could impact application by affecting aircraft engine power, takeoff distance and climb rate or by promoting spray droplet evaporation

- How to determine wind velocity, direction and air density at the application site

- Potential impact of thermals and temperature inversions on aerial pesticide application

- Minimizing drift – The applicator must demonstrate knowledge of factors to consider before and during application, including all of the following:

- How to determine drift potential using a smoke generator

- How to evaluate vertical and horizontal smoke plumes to assess wind direction, speed and concentration

- Selecting techniques that minimize pesticide movement out of the area to be treated

- Documenting special equipment configurations or flight patterns used to reduce off-target pesticide drift.

- Performing aerial application – The applicator must demonstrate competency in performing an aerial pesticide application, including all the following:

- Selecting a flight altitude that minimizes streaking and off-target drift

- Choosing a flight pattern that ensures applicator and bystander safety and proper application

- The importance of engaging and disengaging spray precisely when entering and exiting a predetermined swath pattern

- Tools available to mark swaths such as GPS and flags

- Recordkeeping requirements for aerial pesticide applicators including application conditions if applicable

In November of 2023, EPA announced final approval of 67 updated plans from state, territory, tribal and federal agency certifying authorities.

NAAA is planning on surveying the state ag aviation association directors to determine how the EPA approved plans for each state deal with the requirement for the specialized certification requirements for aerial application.

NAAA has been successful in preserving the Aerial Application Technology Research Unit (AATRU) within USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS). at a time when lawmakers outside of agricultural regions and presently when the Department of Government Efficiency doesn’t understand the importance of agricultural research and its return on investment; however, NAAA has been able to keep aerial application research funding relatively steady by having supportive report language inserted into past appropriation bills and the Farm Bills. Even this current fiscal year (2026) the vote to end the record-long 43-day U.S. government shutdown included a legislative package to fund the Department of Agriculture and the FDA, the Department of Veterans Affairs and military construction projects, and the operations of Congress for the entire 2026 fiscal year. This legislation includes within its committee report—thanks to NAAA’s policy advocacy efforts—language supportive of the Aerial Application Technology Research Unit (AATRU) within USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS). The supportive language reads as follows:

Aerial Application. — The Committee recognizes the importance of aerial application to control crop pests and diseases and to fertilize and seed crops and forests. Aerial application is useful not only to ensure overall food safety and food security, but also to promote public health through improved mosquito control and public health application techniques. The Committee urges ARS to prioritize research focused on optimizing aerial spray technologies for on-target deposition and drift mitigation and to work cooperatively with the Environmental Protection Agency to update their pesticide review methodology.

NAAA will continue to push for NAAA funding of the program so long as the research is being focused on further integrating georeferencing, variable flow control, meteorologic, digital mapping, and aircraft attitude technologies on-board the aircraft to automate the spray systems further resulting in mitigating drift, conserving fuel, and making aerial applications more efficacious, while allowing the pilot to focus on flying the aircraft more safely by allowing that pilot to observing obstacles outside the cockpit.

Favorable committee report language sends a strong message to the USDA to continue to sustain appropriate funding for aerial application research. This message couldn’t be more important as USDA-ARS has had its budget cut over the past few years resulting in the shutdown of 10 research units.

While it is impressive aerial application research funding has remained constant over the years, inflation in salaries, facility maintenance, health care costs and ARS administrative fees have unfortunately resulted in fewer dollars to conduct research at the AATR unit. To adequately fund research costs at the 2002 level the program would need to add two scientists for technical staff supporting the Aerial Application Technology Research program and to initiative to update coding and to conduct data analytics to the AGDISP atmospheric model.

As such NAAA has sought a total increase of $1.75 million for AATRU. Federal aerial application research has significantly benefited the industry over the years. The AATRU has provided sound reason to the public indicating that ag aircraft equipped for crop applications are not a bioterrorism security threat; has provided mobile technologies accounting for equipment and application setup to calculate the most effective and targeted droplet size; and is educating ag aviators on increasing their fuel efficiency, and applied materials efficiency by utilizing precision ag/variable rate technology and how to utilize technology to conduct aerial images and crop-sensing by air. The AATRU is also helping conduct a study to lessen the burdensome effects of EPA’s vegetative strip requirements as part of its endangered species protections by researching how rice levees can serve the same purpose as a vegetative strip.

In addition to lobbying the program on Capitol Hill, NAAA has worn out shoe leather at USDA with key officials over the past few years extolling the benefits of the AATRU unit. Officials include administrators, associate administrator and budget officials of the ARS; individuals at the USDA’s Office of Pest Management Programs; and USDA undersecretaries of research, education, and economics. NAAA has received some positive feedback from the USDA too. ARS officials have told NAAA the language in the appropriation’s report makes the task of keeping the funding for the AATRU unit easier. USDA statistics affirm the necessity for agricultural research, in that for every $1 invested in agricultural research $20 is returned to the economy. Founding father Benjamin Franklin once said, “An investment in knowledge pays the best interest.”

The challenges for all agricultural research and federal discretionary programs are great. With no end in sight on the continual growth of the federal debt—nearly $37 trillion and growing—significant spending cuts have been and will continue to be sought. When it comes to federal agricultural research dollars it is almost inevitable we will continue to see a cinching of budgets because only two percent of our country’s population is involved in agriculture and it is also unlikely this small percentage will be able to influence our nation’s policymakers who set ag research spending budgets. This has been proven recently by challenges involved in enacting a Farm Bill this Congress.

NAAA’s efforts urging the federal government to maintain current levels of aerial application research will continue but, again, it will be a challenging undertaking. To support its goal of increasing funding for the program, NAAA initially established a key coalition of national commodity, farm, and crop protection product manufacturers and applicator groups to join to support funding for additional research. NAAA has also retained the outside lobbying sources of the LeMunyon Group to assist on this project. In addition, efforts to promote the AATRU as a green technology have been used because of the fuel conserved and land and natural resources that are and will continue to be preserved as a result of the judicious use of crop protection products that are able to be made as a result of this important research.

NAAA Newsletters on this Issue

|

2025-12-18 | |

|

2025-11-13 | |

|

2024-07-18 | |

|

2024-05-30 |

Farm Bill Proceeds Out of House Ag Committee with Ag Aviation Regulatory Relief Measures |

|

2023-07-13 |

2024 House Ag Appropriations Bill Again Reports Support of Aerial Application Technology Research |

|

2022-08-04 | |

|

2022-07-14 | |

|

2022-03-31 |

NAAA is closely monitoring the impact of global climate change policy on the agricultural aviation industry, as well as the demand and agricultural practices for crops commonly treated via aerial application.

- January 2021 – The EPA adopted airplane greenhouse gas emission standards, but because these do not apply to propeller-driven airplanes with a maximum takeoff weight under 19,000 pounds, current type-certified ag aircraft are not affected.

- March 2021 – The USDA requested stakeholder input on a “climate smart agricultural and forestry strategy.” NAAA submitted comments detailing the efficacy and timeliness of aerial applications, which protect the environment and reduce climate change impacts. NAAA also highlighted the contribution of aerial application to improving the environment by seeding cover crops. NAAA suggested supporting policies that increase the number of no-till or reduced till acres and cover crop acres, as both activities reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

According to ethanol industry experts, biofuel has the potential to be a 30-billion-gallon market long-term in the U.S. Most of finished motor gasoline sold in the United States is about 10% fuel ethanol by volume. Similarly, the desire for more environmentally friendly fuels has increased demand for soybean based biodiesel and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF).

In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) authorized $783 billion in federal spending addressing energy and climate change. This resulted in the new, two-year 40(b) tax credit for farmers and processors of SAF. By way of the Renewable Fuel Standard—the federal program that requires transportation fuel sold in the U.S. to contain a minimum volume of renewable fuels—a minimum $1.25 per gallon tax credit now exists for SAF derived from soy oil.

The tax credit was expanded in 2023 and 2024 if the fuel reduces lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50 percent. To achieve this reduced carbon intensity (CI) score for soy oil-based feedstock, an additional pathway was created, stipulating the utilization of the climate-smart agricultural (CSA) practices of no-till planting and cover cropping—a common application executed by ag aviators making their services even more valuable to soybean farmers. The 40(b) tax credit will expire on January 1, 2025 and be replaced with 45(z), shifting the formula to take CI into greater account for calculating total carbon reduction.

To assist farmers with CSA conservation practices, the IRA added almost $15 billion in producer-led grants and cost-share programs, including the USDA’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), and Conservation Technical Assistance (CTA). Farmers can access funds directly to support no-till and cover cropping.

Aerial applicators can help farmers in their efforts to become eligible for SAF tax credits by employing CSA practices such as applying cover crops Additionally, cover crops seeded by aerial application may preclude the need for seed drilling and therefore, may also check the box for no-till planting.

Escalating demand to meet 2030 and 2050 SAF goals will continue to necessitate an increase in yield for oilseed crops, without adding significant acreage for planting. Effective crop protection strategies will be critical to achieving these yields, and the aerial application of fungicide for soybeans will be a key component.

As climate-smart agricultural practices proliferate and the U.S. relies more heavily on crops like soybeans to decarbonize agriculture and aviation, the relationship between farmers and aerial applicators should become increasingly important. Conveying this connection and helping farmers understand the stakes of the SAF Grand Challenge can help ensure that the aerial application industry is at the table and fully integrated into the investments for growing the SAF market. The global SAF market is expected to grow significantly as airlines stive to meet both environmental commitments and government regulations.

In January of 2026, Republican U.S. lawmakers created a task force to study potential year-round sales of higher-ethanol E15 gasoline blends in the U.S., after an attempt to pass such legislation in a funding bill fell through. Farm groups and Midwest ethanol advocates blasted the decision to form a task force instead of passing legislation, calling it a blow to American farmers already stung by low prices, uncertain global trade, and a lack of clarity over U.S. biofuels policies.

Farm interests want year-round sales of E15 – which has higher ethanol content than the E10 now widely available at the pumps. The move would boost demand for corn, ethanol’s primary ingredient. Oil refiners have resisted increased biofuel blending mandates in the past, citing higher costs.

E15 sales are currently limited during summer months due to air quality regulations.

The compromise deal would establish a so-called “E-15 Rural Domestic Energy Council” to investigate topics including the sale of E15, U.S. refining capacity, biofuel blending credits and other issues and to recommend legislation by mid-February.

|

2024-08-15 |

Cover Crops Press Release Available for Members to Send to Local Media Outlets |

|

2024-05-23 | |

|

2023-09-28 |

NAAA Earns Solid Media Coverage for Cover Crops Press Release |

|

2023-09-07 | |

|

2022-10-27 |

Honeywell Unveils Ethanol-to-Jet Fuel Process to Tap Sustainable Aviation Fuel Demand |

|

2022-05-05 | |

|

2022-02-25 | |

|

2022-01-20 |

Currently, aviation gasoline (AvGas, 100LL most commonly) is the only transportation fuel in the United States that contains TetraEthyl Lead (TEL), a lead-based additive that has been added to AvGas since 1921 to boost octane ratings and prevent engine damage and knocking at higher power settings. In response to the evolving market factors and public health considerations, the FAA has initiated transition efforts from 100LL to unleaded aviation fuels. The primary market factor is the supply of TEL additive. There is a single source TEL provider for the U.S. market. This provider has indicated an eventual end of production of the TEL additive, which will affect the global market. The only other potential sources for TEL could lead to reliance on sources such as China, resulting in potential supply chain concerns as well as long-term availability issues. These market factors are further influenced by public health concerns from exposure to lead, motivating the FAA and the aviation community to seek alternative fuels.

The agricultural aviation industry’s continued shift toward Jet A powered turbine engines has reduced the number of piston (AvGas) hours flown to less than 15% of the fleet. Still, the industry absolutely does not want to lose those aircraft or the acres that they treat. These piston engine aircraft are also optimal for training new ag pilots. NAAA maintains that an efficient, practical and widely available alternative to AvGas must be available before regulations target any restriction on its use in agriculture.

- In 2012, FAA authorized the Unleaded AvGas Transition Aviation Rulemaking Committee (UAT ARC) to investigate, prioritize, and summarize the current issues relating to the transition to an unleaded AvGas, and to recommend the actions necessary to investigate and resolve these issues. The UAT ARC produced a comprehensive report and made them available to the public. Pursuant to these recommendations the FAA and industry established a program called Piston Aviation Fuels Initiative (PAFI) to support the evaluation of candidate unleaded fuels to replace approved leaded AvGas. The ultimate objective of the program is to qualify a fleet-wide solution.

- In February 2022, the FAA joined aviation and petroleum industry stakeholders announcing the initiative to Eliminate Aviation Gasoline Lead Emissions (EAGLE), targeting a transition to lead-free aviation fuels for piston-engine aircraft by the end of 2030.

- In October 2023, the EPA issued a final determination that lead emissions from aircraft engines that operate on leaded fuel endangers public health under §231(a) of the Clean Air Act. Consequently, both the EPA and FAA are now subject to a duty to promulgate regulatory standards addressing aircraft lead emissions.

- The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 supported the EAGLE goal, while clarifying that airport owners and operators must not restrict the continued availability of 100LL until the end of 2030, or when a certified unleaded alternative is available at airports.

Finding replacement unleaded fuel involves in-depth testing and evaluation of many fuel characteristics such as performance, detonation resistance, materials compatibility, durability, maintenance impacts, and the potential need for related aircraft alterations. As of September 2025, in the U.S., there are three candidate high-octane unleaded fuels at various stages of development and deployment.

- G100UL – General Aviation Modifications, Inc. (GAMI)

- 100R – Swift Fuels

- UL100E – LyondellBassell/VP Racing

Each manufacturer has chosen a unique path forward based on type of Specification (i.e. independent, ASTM), and type of FAA Authorization (STC, AML STC, Fleet Authorization).

In January 2026, FAA released their Draft Transition Plan to Unleaded Aviation Gasoline for public comment. This document lays out FAA’s intended role and timeline in the transition to meet the 2030 target date. It also details the current status of each candidate fuel.

The Federal Insecticide Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) regulates pesticide labeling, distribution, sale, and use in the United States, ensuring stringent safety standards and oversight. All pesticides used in the country must be registered by the EPA, which protects the food supply, people, pets, waterways, trees, and wildlife from pests and diseases. State lead agencies regulate pesticides, but a patchwork of laws often conflicts with each other, creating confusion for aerial applicators and their customers. Some states lack a pesticide preemption law, allowing individual localities to regulate pesticides differently, creating unequal protection for citizens and crops based on their zip code.

Legislation is needed to clarify the exclusive role of the EPA and state lead agencies to prevent conflicting regulatory restrictions without scientific assessment, economic analysis, consideration of the consequences to the food supply, or responsibility of public health agencies to control disease vectors. This will ensure that those with expertise at state lead agencies and the EPA determine pesticide usage. State lead agencies have worked with the EPA since the 1970s to administer and enforce FIFRA laws and support the development of scientifically based pesticide labels. Forty-six states have adopted some form of pesticide preemption and are working cooperatively with local officials to enforce robust oversight of state pesticide laws.

- NAAA has joined national and state ag and pesticide user groups to the House and Senate Ag Committee chairpersons and ranking members expressing strong support for including in the the next Farm Bill reauthorization language under FIFRA codifying state oversight of pesticides at the state level.

- The 2018 Farm Bill was extended via the American Relief Act until September 30, 2025.

- The biggest challenge will be to secure agreement on topline spending for agriculture programs, as well as decide how to handle the politically charged debate around SNAP (food stamps), which comprise a majority of Farm Bill spending.

- In July 2025, U.S. Senator Cory Booker (D‑NJ) introduced the Pesticide Injury Accountability Act of 2025. The bill seeks to amend FIFRA by establishing a federal private right of action. This would allow individuals to sue pesticide manufacturers in federal court—regardless of existing state laws or federal approvals—posing a significant risk to the stability of the pesticide registration system. Although framed as a means to enhance accountability, the legislation opens the door to increased litigation and politicized decision-making, rather than relying on the science-based risk assessments conducted by EPA under FIFRA. Moreover, past proposals from Senator Booker have aligned closely with European Union-style pesticide bans and hazard-based decision-making models that NAAA has consistently opposed due to their departure from evidence-based regulatory principles. Booker and twenty Senate colleagues also sent a letter urging Senate leadership to preserve state and local authority over pesticide regulation in the upcoming Farm Bill or related legislation. While framed as protecting community-level safeguards, the letter directly opposes efforts to include federal pesticide preemption in the Farm Bill, a longstanding priority for NAAA and other stakeholders working to ensure consistent, science-based pesticide oversight, rather than emotion-based, untrained decision-making that stems from local jurisdictions. Weakening federal preemption threatens to create a patchwork of conflicting local regulations, undermining applicators’ ability to operate effectively and predictably across jurisdictions.

NAAA has been meeting with Hill staff as part of a larger preemption coalition to have language inserted into the Farm Bill to preserve FIFRA’s preemption primacy and has been told by staff at both the House and Senate Agriculture Committees that preemption language will be included within its initial draft.

|

2025-07-31 |

Pesticide Litigation and Local Jurisdiction Efforts Advocated by Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) |

|

2024-06-20 | |

|

2023-03-16 | |

|

2022-12-01 |

NAAA Joins in Urging Congress to Reaffirm EPA’s Preemptive Role Regulating Pesticides |

|

2022-06-23 | |

|

2022-06-09 | |

|

2022-04-14 |

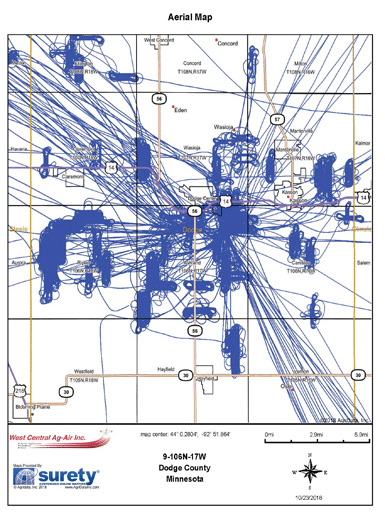

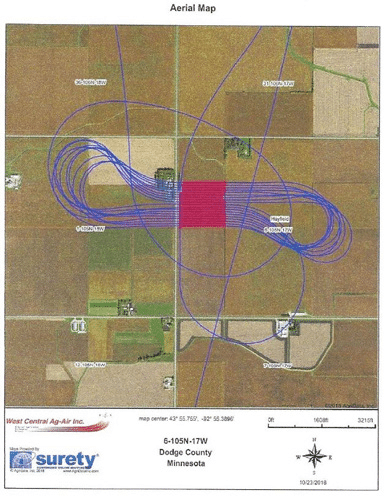

FieldWatch was designed by staff from Purdue University with the intent of helping pesticide applicators, specialty crop growers, and beekeepers communicate more effectively to protect pesticide-sensitive areas. The site features a Google Maps™ interface that shows applicators the locations of registered areas so they can take the appropriate precautions before they spray. It also provides contact information to encourage communications between the various parties.

FieldWatch (originally known as DriftWatch) was spun off as an independent nonprofit organization affiliated with but not formally part of Purdue University. FieldWatch is led by a CEO and is governed by an executive board. There are also groups assigned for each of major stakeholders, including an applicator which includes a representative for aerial applicators selected by NAAA. NAAA has long supported FieldWatch had been heavily involved in its development and expansion.

FieldWatch is the name of the overall organization and is composed of the following individual registries:

- BeeCheck® is a registry specific to apiaries where beekeepers can register and map their apiaries

- DriftWatch is where commercial specialty crop producers can register and map the locations of their specialty crops.

- CropCheck™ is a pilot program to map row crops in states that have volunteered to participate.